Raising Hell in the Orchestra Pit

How Christopher Young Unlocked the Puzzle of a Classic Horror Score on a Shoestring Budget

The 1980s didn’t invent the horror movie genre, but there’s little denying that horror movies characterized the ‘80s in a way that remains influential. For many film fans, the names “Michael Myers”, “Jason Vorhees”, and “Freddy Krueger” are the standard bearers for horror films of the decade. Countless lesser names flooded the C-movie (or lower) rack at your local video rental store on any given Saturday night as well.

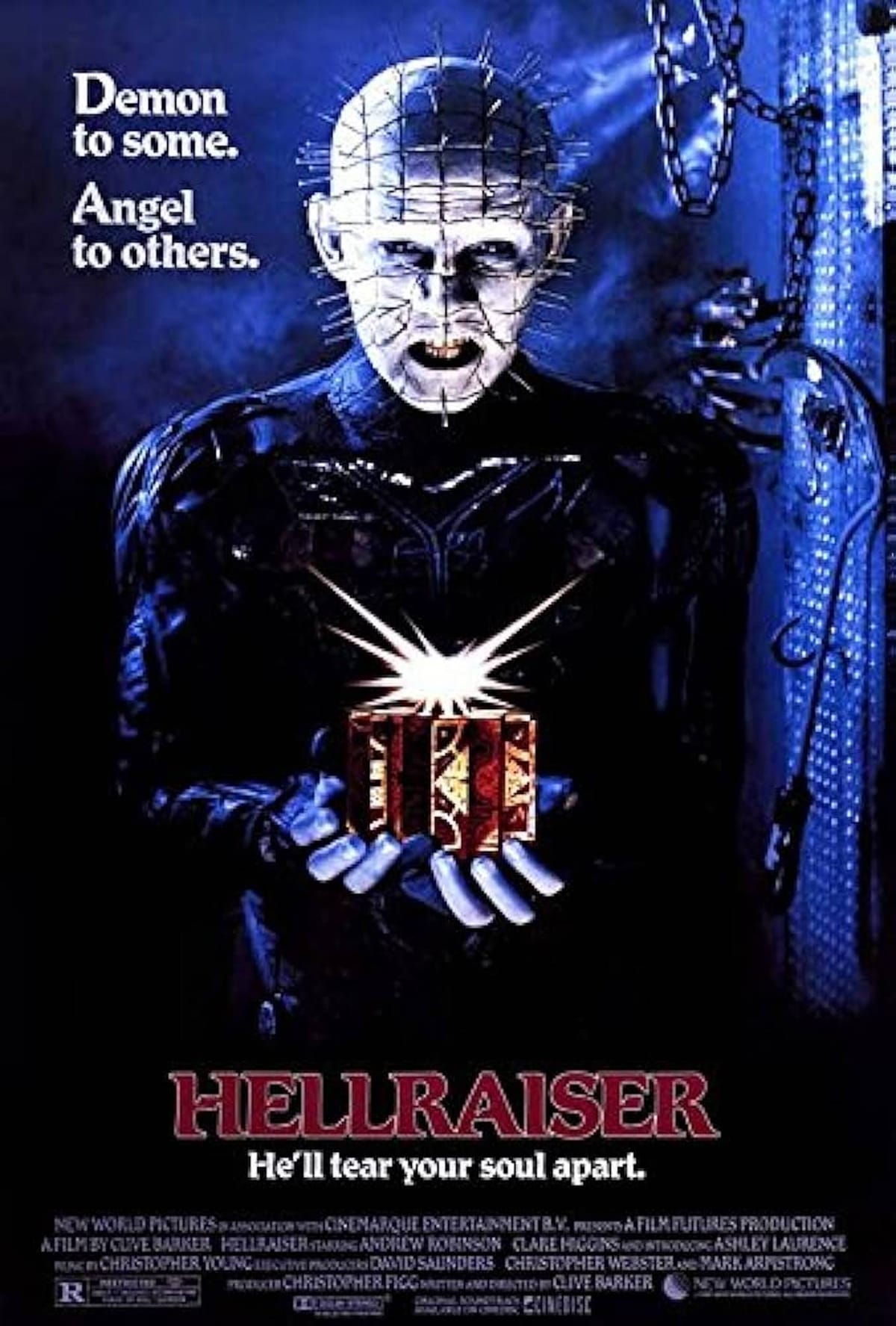

A relative latecomer to the 1980s horror scene was a memorable character whose name bore no on-screen mention but became affectionately known as “Pinhead” to followers of the genre. Pinhead was, of course, the non-antagonist of “Hellraiser”, the 1987 directorial debut of horror author Clive Barker.

“Hellraiser” was unquestionably a low-budget movie by any standard, but it rose above its $1 million budget to become a highly-regarded horror classic. No small part of the film’s longevity is Christopher Young’s genre-bending score.

Young’s score boosted “Hellraiser” well above its budget with a distinctly more mature feel and serious tone. His score both matched and legitimized Barker’s avant-garde storytelling and remains a key reason for the film’s longevity as a beloved horror classic.

But it wasn’t easy getting there.

Here’s the tale of how “Hellraiser” transcended its financial limitations and how its score left a mark on the horror genre that remains to this day.

From Synths to Symphonies

John Carpenter established many of the horror tropes we continue to see today with 1978’s “Halloween”. A colossal hit on the smallest of budgets, one of the film's most highly praised elements was the eerie synthesizer score created by Carpenter himself. While he loved scoring his own movies, it was initially out of the necessity of having no budget to hire a composer.

Conspicuous use of synth scores throughout the 1980s became standard operating procedure for many of the low-concept, low-budget horror flicks that followed.

Yet this wasn’t universally so.

Not all ‘80s horror movies were low-budget slasher affairs. The 1980s was also a boom time for higher-end, higher-concept horror such as 1981’s “An American Werewolf in London”, 1982’s “Poltergeist”, 1986’s “The Fly”, and 1987’s “Predator”, just to name a few.

In addition to being massive commercial successes, these films were all accompanied by orchestral scores from name-brand composers such as Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Goldsmith, Howard Shore, and Alan Silvestri, respectively.

But what about when you have a high-concept film saddled with a low-concept budget?

This was the very problem faced by long-time author but first-time film director Clive Barker when it came to directing “Hellraiser.”

The Future of Horror

Born in Liverpool, England in 1952, Clive Barker was drawn to the creative arts at a young age. At only 15 years old, he was heavily involved in high school theater with plays such as “Inferno” and, at 22, was collaborating with local theater companies. By 1976, he had sole writing credit for Mute Pantomime Theater’s productions of his plays. In 1978, he established the London-based Dog Company Theater to tour and stage performances of his original works, such as “History of the Devil.”

With a masterful blend of uncomfortable eroticism and elegantly macabre prose, Barker soon transmuted his playwriting skills into short stories. His friend, fellow horror author Ramsey Campbell, proved to be an invaluable connection in getting Barker’s stories into print with Sphere Books.

Barker took the literary world by storm in 1984 with his first collection of short stories, “Books of Blood, Volume One”, with five more volumes published by 1985. Barker released his first full-length novel that same year with his New York Times bestselling “The Damnation Game.”

But it was an erotic horror novella he wrote in 1986 that would lead to his biggest career breakthrough.

Young but Hungry

While Clive Barker was coming up in the literary world, American composer Christopher Young was busy cutting his teeth in his future career as well.

Born in 1958, New Jersey native Christopher Young moved to Los Angeles in 1980 after graduating with a BA in music from Massachusetts Hampshire College and post-grad work at North Texas State University. A chance encounter with the film music of Bernard Herrmann changed the course of the then-jazz drummer’s vocation and introduced Young to film scoring.

He soon began attending UCLA Film School and found a mentor in film composer David Raksin. Raksin wasn’t a fan of Young’s early efforts, almost prompting the fledgling composer to quit at the starting line.

Young stuck with it and wound up networking with several up-and-coming filmmakers who would be figurative in launching his film score career.

His first film score was for the 1981 student film “The Dorm That Dripped Blood”, which went on to enjoy a nominally successful theatrical release in 1983. With a paltry budget of $150,000, one could easily assume Young would have leaned hard on what he could accomplish by himself with a synth.

Instead, Young tipped his hat toward Bernard Herrmann, elevating the film with a surprisingly effective mostly-strings score. From there, Young worked his way up on a variety of low-budget, low-profile films. He struck gold with 1985’s mega-hit “A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge.”

Elsewhere, “Hellraiser”, much like one of its chief antagonists, was slowly congealing.

Sadomasochists From Hell

While writing and directing plays was nothing new for Barker, directing a film was not yet something he’d added to his repertoire.

His connections helped him scoop up a couple of screenwriting credits. His first was the original screenplay “Underworld” in 1985 (released as “Transmutations” in the United States), followed in 1986 by “Rawhead Rex”, an adaptation from “Books of Blood, Volume Three”.

Barker wasn’t happy with the final product of either production, but especially so with “Underworld”. The obscurity of the film helped Barker avoid a potentially career-killing fiasco and convinced him that he wanted to be more hands-on with future films that bore his name.

After conferring with film producer Christopher Figg, all Barker would need to get into the director’s chair to mastermind one of his own stories was a budget of $1 million for a house, unknown actors, and some monsters.

Barker soon wrote “The Hellbound Heart” specifically to check all the recommended boxes.

And, given that he flirted with the idea of calling his debut film “Sadomasochists From Hell”, it was probably a prudent move to helm the project himself. It might have been a cheeky idea for a movie title, but it was also an apt description of the film Barker wanted to make.

“The Hellbound Heart” explores themes of seduction, desire, pain, and the thin line between pleasure and suffering… And it was all inspired by Barker’s own experiences as a high-end male escort in the 1970s. Those encounters informed the subversive eroticism of Barker’s work, with a hardcore underground S&M club in New York factoring large in what would become one of his most famous tales.

Barker wanted to call the film “Hellbound”, but enthusiastically embraced “Hellraiser” at Figg’s suggestion.

Hell Is Other People

While “Hellraiser” looked like a prime opportunity to bring British horror cinema back into fashion, no British film studios were willing to step up to the film’s controversial themes.

Roger Corman’s New World Pictures wasn’t so squeamish, so the Los Angeles-based production company agreed to fund it to the underwhelming tune of $900,000.

The challenges of a low budget continually weighed on the production of “Hellraiser”. Barker pulled in many of his friends from his theater days to fill roles.

For the film’s score, Barker wanted his friends in local industrial band Coil to create the sonic backdrop. Excited to get started, Coil began working on the score, which Barker wanted somewhere between “Carrie” and “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” in tone.

By this point, New World Pictures had started picking up on the idea that they might have a hit on their hands and started taking a more active role in the production.

New World Pictures head of post-production (and future director of the first “Hellraiser” sequel) Tony Randel wanted a score that would give the film broader appeal. Randel and Christopher Young had a good working relationship, with Young already having scored several other New World Pictures titles.

Randel knew that Young could slam-dunk it… And do it for pennies on the dollar.

Out of courtesy to Barker, Randel met with Coil all the same. He pulled no punches, hitting them with technical questions about producing film music that they could not answer.

To their credit, Coil said they'd give it their best shot… And this is where stories differ.

Did Coil dispiritedly bow out only hours after the meeting? Indeed they did, according to Randel.But according to Coil’s Stephen Thrower, they were more fired than anything. To this day, Thrower maintains that the promise of additional funding for special effects was too much for Barker to resist… As long as he agreed to go with the studio’s choice of composers.

Keeping Score

Young preferred using orchestras in his scores from day one. Yet ironically, his first impulse for “Hellraiser” was to break out the synth. Having read Barker’s “Books of Blood”, he imagined an orchestral score for “Hellraiser” as dark, complex, twisted, bombastic… And just too much for the setting.

He felt like there wasn’t enough room for the blast of a full orchestra given that most of the action took place in a single house. He felt a synth could be more complementary to the movie’s intimate setting.

But the producers wanted an orchestral score that would “tug at the heartstrings”, twisted though they may be.

Barker and Young met face-to-face in New York to hammer it out. Barker quickly dispelled all notions that he wanted anything so in-your-face for his horror film as Young had assumed.

On the contrary, Barker told Young he wanted to be seduced by the music. Barker maintained that “Hellraiser” was a love story, a film about being seduced by pleasure and power, and the lengths to which people will go to attain them. This required a delicate touch, not a ham-fisted one… Barker held that the key to seduction was a few well-chosen words in the right place.

Young got the message loud and clear. From that point on, he collaborated with Barker by setting the phone on his piano in LA and workshopped his ideas in real time with Barker in England.

Hellbound for Success

Debuting in London on September 7, 1987, “Hellraiser” was an enormous financial success, pulling in almost $15 million against its $1 million budget.

Young’s score was widely praised, but it wasn’t until his score for 1988’s “Hellbound: Hellraiser II” that he won a Saturn Award for his troubles. Indeed, he has a long list of nominations and wins over a prolific career spanning nearly 100 works, and was awarded Composer of the Year, Composition of the Year, and Best Original Score by the International Film Music Critics Association in 2023.

For Young, his most poignant memory of “Hellraiser” was sitting in a cramped editing booth in New Orleans during post-production. He was moved to tears when he heard his waltz play over the classic scene of a character being gruesomely resurrected.

That was the moment he felt sure that writing film scores was what he was supposed to be doing with his life.

For Barker’s part, he signed over his rights before the movie was even released, effectively cutting himself out of a franchise that he birthed… Including input on sequels and their profits.

Barker regained his US franchise rights in 2020, just in time to have a hand in producing the 2022 “Hellraiser” reboot. Composer Ben Lovett created an outstanding original work of his own while paying homage to Young’s scores for both “Hellraiser” and “Hellbound: Hellraiser II.”

Decades later, the legacy of Christopher Young’s career-defining breakout score seems to be just getting started.

Are you enjoyng our work?

If so, please support our focus on independent artists, thinkers and creators.

Here's how:

If financial support is not right for you, please continue to enjoy our work and

sign up for free updates.

Comments ()